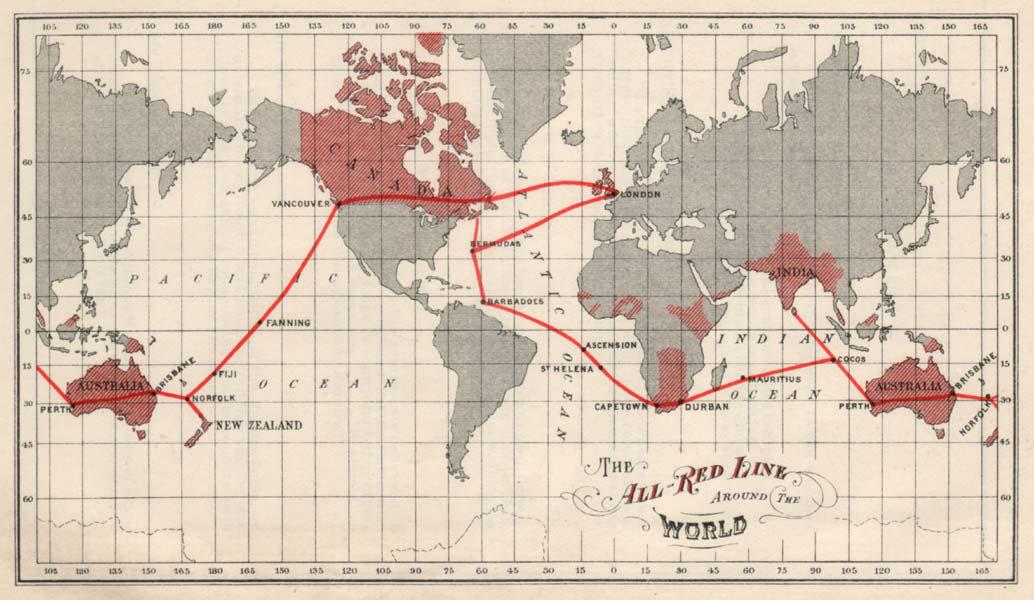

Map by George Johnson (public domain image)

Look at this remarkable map from 1902, and you’re seeing something more revolutionary than most people realize.

Those red lines crisscrossing the oceans weren’t just cables. They were the Victorian internet, connecting the British Empire in ways that would have seemed like magic just decades earlier.

The Empire’s Nervous System

The “All Red Line” was Britain’s audacious project to link every corner of its empire with submarine telegraph cables.

Red, of course, represented British territory on maps of the era, and the goal was simple yet staggering: create a communications network that touched only British soil and seabed, avoiding potential enemies who might cut the lines during wartime.

A Web of Copper and Ambition

The routes tell fascinating stories. Vancouver to London via Bermuda and Halifax. Australia connected through multiple redundant paths via Norfolk Island, Fiji, and Fanning Island in the Pacific. Cape Town linked to Mumbai via Mauritius. Every major colonial outpost had its lifeline back to London.

These weren’t trivial engineering projects. Laying cable across thousands of miles of ocean floor required specially built ships, new technologies for insulation and signal amplification, and enormous capital investment.

The cables themselves were marvels: copper cores wrapped in gutta-percha insulation, armored with iron wire, and heavy enough to sink to depths of several miles.

Speed of Empire

Before these cables, sending a message from London to Sydney could take months by ship. After 1902, it took minutes.

Military orders, commodity prices, diplomatic communications, and personal telegrams could race around the globe at the speed of electricity. This transformed everything from warfare to finance to how families stayed connected across continents.

The strategic importance was immense. Britain could coordinate naval movements, receive intelligence, and manage colonial affairs in near real time. Other nations watched with a mixture of admiration and alarm as Britain wired its empire together into a single, responsive organism.

Legacy in the Ocean

What happened to all those cables? Many of them are still down there, buried in marine sediment or encrusted with coral. Modern fiber optic cables often follow similar routes, because the geography of the ocean floor hasn’t changed. The engineers of 1902 chose their paths well.

The All Red Line also represented the peak of a certain kind of globalization: one centered on empire, designed for control as much as communication, and built to exclude as much as to connect. Within a few decades, two world wars would shatter many assumptions about how the world worked, but the need for global communication only intensified.

Today’s internet is the descendant of these cables. The map reminds us that our connected world didn’t emerge from nowhere. It was built, wire by wire, by people who understood that information is power, and that controlling how it flows shapes the destiny of nations.

Help us out by sharing this map: